|

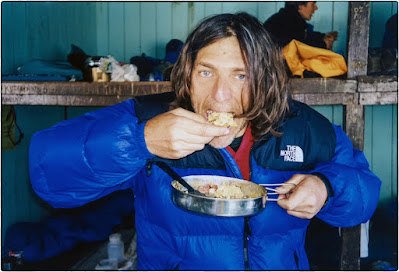

| Kentucky and I near the peak of Malinche |

The hike the next day was a long, gradually steepening slope from about 10,500 feet to the 14,500 foot peak. It was many miles of walking before it became a slightly technical climb meaning you had to use your hands. It was a chance to get our legs and lungs and heads in shape for the bigger climb to come. In the morning, we made a quick breakfast and readied day packs with water bottles and snacks. We would be hiking trails through beautiful pine forests that gave way higher up to small shrubs and yellow Montane grass, then to sheer rock. About once an hour, we would take breaks to drink water and eat a handful of gorp.

Parks' two clients, Apopka and Kentucky, couldn't have been different. Apopka was making big money building cell towers which were just beginning to smother the landscape for the coming cellular age. He was a roughneck who climbed towers but had never climbed in the mountains before. He seemed tough, and had had bought all the best climbing gear. Indeed, in that he was enviable. Otherwise, though, not so much. He was cocky and couldn't wait to show how tough he was. But as said, he had never been in the mountains, and being at altitude is a very different thing.

Kentucky, on the other hand, was educated and a financier. He was married and seemed like a good family man. On the way up Malinche, having been here before, I advised them not to get out of breath, that on the big climb, once you had depleted yourself, you never recovered. There just wasn't enough oxygen. Indeed, at 14,000 feet, there was only half the oxygen there was at sea level. Above 16,000 feet, I had heard, the bacteria in your mouth began to die. It was important to drink plenty of water to ward off edema of both the lungs and the brain. I knew the consequences of all these things very well.

Kentucky was willing to listen, but Apopka didn't like me, I could tell. He was a redneck and saw me as a hippie sissy, I gathered. I was just the type of person he and his redneck friends made derisive jokes about. It was o.k. with me, for I hadn't much love for him nor his type, either. And so, Kentucky and I paced ourselves together while Apopka ran up behind Parks who was always somewhere up ahead.

Near the top, Apopka was struggling, but 14,500 is doable for just about anyone, so we all made it to the peak around the same time. Parks, of course, was very spiritual about the mountains, and so he insisted we all have a moment of silent meditation as we looked over the plains far below stretching out to Mexico's three highest volcanoes which were visible that day many miles away--Iztaccíhuatl, Popocatépetl, and Pico de Orizaba, or Citlaltépetl as it is also known.

I always hate coming back from the peak. I have never been good at going down the mountain. Indeed, I am always the slowest. It is easy to get hurt coming down as you are pretty well exhausted and you begin to let yourself get careless. You can step on a loose boulder or rock and break a leg or twist an ankle or even, on the most rugged mountains, begin a slide that might go on for thousands of feet. I was pretty tired by the time we got back to camp and ready for a shower and a hot meal. Santiago had things packed up, so we hiked down to where we could grab taxis back to our hotel.

That night, there was a festival in the town plaza, and so we wandered about eating street food and flirting with the girls. Mexican street festivals were wonderfully exotic things to Americans back then with their strings of lights and colorful booths and the vibrant energy of the crowd. There were games of strength and games of chance, and though I'd been to many of them over the years, I always felt a surge of excitement when I was there.

We stopped at a booth to get something to eat. Street food is o.k. as long as it's cooked, but we had always avoided the raw stuff, even the sauces that looked so delicious and inviting. This is what I suggested to Kentucky and Apopka.

"Oh, man. . . you think you know everything," Apopka spat at me with venom. "You gonna tell me what to eat, too?"

"Nope. You go ahead and eat what you want. I'm just saying I wouldn't, but I'm sure you'll enjoy it."

Kentucky prudently followed my lead and we ate grilled skewers of chicken and tortillas with string cheese and a beer.

The next day, we were picked up at our hotel by Señor Gutez. He had a service ferrying climbers to the hut at the base of Pico de Orizaba. He was a climber himself and had made a successful business from his mountain services. We loaded into his truck for the long ride.

Along the way we stopped for supplies. Parks wasn't into eating freeze dried meals. We bought garlic and cheese and noodles and eggs and dried meats, avocados and oranges for making snacks and soups and solid dishes. Parks wanted to be as comfortable on the mountain as possible to conserve his energy. Good food was a big part of that.

After a few hours, the hut came into view. We would stay there a night and a day and part of the next night, rising at midnight to begin the climb. We were not the only ones at the hut, however. That same day, two teams of climbers had come, one a group of mountain rescue guides from New Mexico and the other a ski team from Colorado. It was a full house and we were all heading up the mountain on the same day.

|

| The hut at Orizaba |

The hut was just a basic structure without water or heat, just some wooden bunk platforms on which to throw a sleeping bag. Days were spent sorting gear outside, taking short walks, playing cards, and cooking. The other climbing teams were young, and they were excited. Parks and I had been on this mountain before and were much less animated than they. I had a bunk below one of the fellows from Colorado. It was in the bunks that we would huddle as a group to play cards or just sit and talk. The boys for Colorado, however, were like little kids and kept knocking what I assumed was rat shit down from between the boards, and so I yelled up at them, "If you little fuckers keep knocking rat shit down on me, there's going to be trouble. Knock it off."

"You old guys are mean," they laughed. I had to laugh, too. Yea, I thought, I guess so.

There was an outhouse down the mountain a bit, and all day I noticed that Apopka had been heading that way. In the afternoon, we cooked up some omelets with eggs, cheese, garlic, and avocado. Apopka, though, didn't eat any. He said he wasn't hungry. After we had cleaned up, we all sat down to play a game of hearts. I didn't know the game, so they taught me the rules. The strategy, though, was another thing. We played for points and the game ended when someone reached a certain number. We decided that the loser would have to hike down to the stream and fill the neoprene water jugs, a hated task.

I was losing badly at first, but I was beginning to learn the game, and as we came to what was probably going to be the last hand--as one of the fellows was close to the ultimate score--I was had the fewest points, a bit behind Apopka. It was getting dark and cold and the last thing in the world I wanted to do just then was walk down the hill, get wet, and trudge back the steep slope carrying heavy water bags to the hut. I was sick with thinking of it.

So we played the last hand and cards were being thrown. And, I guess, God was on my side because I had the best play, got the most points, and passed Apopka up by a mile. He was furious. He looked at me with what could not be mistaken for anything but hatred and rage. And I grinned. Oh, god, I was happy not to have to walk down that hill, but I was thrilled that it was going to be Apopka. No matter if we made it to the peak or not, the trip was now going to be a success.

It turned out that Apopka was sick and would not be going with us at midnight. He'd been shitting and puking all day. I thought to wonder out loud if he thought it might have been the carnival food he had decided to eat, but I was afraid he might put his ice pick through my heart, so I simply looked at Kentucky, and nodded with a big grin.

By six o'clock, it was freezing and everyone had climbed into their bags for the night, piss bottles at the ready. You don't sleep well at altitude, and every time you wake, you drink some water. It is very important to stay as hydrated as possible, but it is also important to pee. It is all part of avoiding edema. Some climbers take a diuretic as were some of the kids in the other climbing groups, but Parks was convinced it was much better to simply drink more water than you wanted. I'd done both and was convinced he was right. Either way, though, you constantly have to pee and it is too cold to go out, so you always have a gallon jug to pee into without getting up. I have often nearly filled the jug before the end of the night.

At midnight, watch alarms started to buzz, and everyone began to roll out of their bunks and put on their gear.

"Come on, you guys," Park said, "We don't want to be behind these jokers. We need to be the first ones on the mountain."

And so we were. Headlamps lit the eerie mountain landscape, but the night was clear and there was a good moon, and so by and large, we shut them off and let our eyes adjust. Slow steps. Parks and Santiago were in far better mountain shape, of course, and they had to wait for Kentucky and I to catch up.

"Remember," I said, "don't let yourself start to pant. Keep a steady pace. You won't make it if you don't."

Parks was leading and would get ahead and wait where we could see him, but Santiago hadn't worn enough clothing and couldn't stop or he would get too cold, so he kept walking, doing laps around us. I realized it would be impossible for me to keep up with him on a mountain.

And so we ascended in the dark, Parks ahead, Kentucky and I slowly rising, Santiago doing laps. The rock turned to snow and then to ice, and we roped up in case anyone had a slip and fall. I don't know if Santiago or Parks would have roped up if they were on their own, but it was what you did as a group when there was any danger of a fall in an ice field. But we were too slow for Santiago. He had to unclip and keep moving. I was feeling good, and it seemed to me that we were moving pretty quickly. And then, far below us below a shelf of clouds, there was light. The sun was coming up miraculously, beautifully, lighting the mountain from below. I looked up and saw what looked like a peak.

"What's that?" I asked Parks.

"That is where we are going," he said.

"That's the peak?"

"That's the peak."

Holy shit, holy shit, we had really made good time. The goal was to be on top and heading down by noon. If we weren't there by noon, we would simply turn around. But this was crazy. The sun was rising and we were already there.

"Hey, Kentucky. . . there's the peak!"

He looked up and grinned.

Mountain climbing is funny. You never spend much time on top. You get there, you look around, and you head back down. There is really nothing to do there but look out over the valley floor which this morning was shrouded in clouds around ten thousand feet. Somewhere below us, a jetliner was making its descent into Mexico City.

As we turned to head down, we could see the other groups far below.

"Fuck yea," I said. "Old men kicked their asses. Ha!"

Parks had been right about not getting caught behind them.

An hour or so later, as we made our way past them, I said, "Not much further. You guys are almost there."

Tired faces looked up and nodded.

"We left you some coffee on the peak," I added like an asshole.

We were back to the hut before the made the summit, but we learned that one of the climbers had suffered brain edema so badly he lost consciousness. They were waiting on a truck to come to take him down.

Feeling like a victor, I wanted to tell Apopka all about the climb as we packed our gear and got ready to go. Gutez, however, wouldn't be up until the afternoon, so we sat with our backs to the hut in the sun and ate all the food we had left.

We saw the two other groups descending when Gutez appeared. We threw our bags into the truck. We were staying at his place that night. We would be back to town before supper.

No comments:

Post a Comment